The rich Hansard corpus of over 18 million words cries out for analysis. While it’s not exactly verbatim, the corpus satisfactorily represents how MPs talk about the topics of parliamentary debates, even with the repetitions and pauses edited out. A rich and accurate resource like this can provide answers to a myriad of questions. For our Hansard at Huddersfield website, we are exploring what kinds of questions can be answered using the simplified corpus linguistic methodology that will be incorporated. We thought that examples of linguistic research using this methodology might spark ideas about the questions you may be able to answer using our Hansard website.

One incentive driving linguistic researchers to use corpus linguistic methodology is that the software makes it easy to identify the degree of interest MPs will have had in a particular concern over an extended period of time. The results of such a query can then be cross-referenced with historical events to understand why MPs were so keen (or not) to discuss that topic during that period.

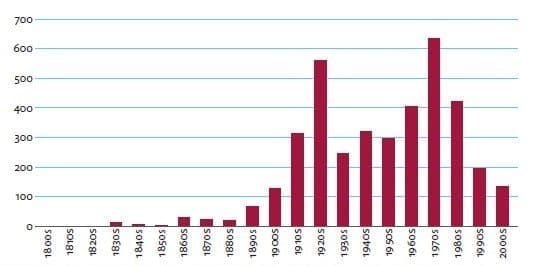

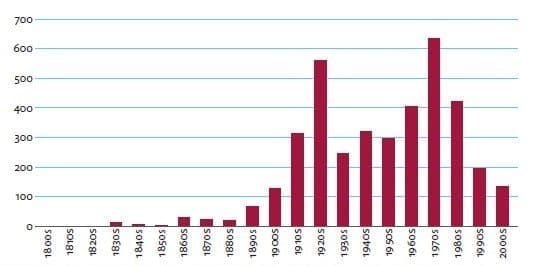

Three linguistic researchers, Jane Demmen, Lesley Jeffries and Brian Walker, tried to answer this type of question in a recent study. They used corpus linguistic methodology to investigate ‘labour-relations’ in the House of Commons debates over the 19th and 20th centuries. ‘Labour-relations’ refers to “the notion that both employers and workers have rights and responsibilities which can be negotiated using the collective bargaining power of trade unions” (Demmen et al. 2018). They realised that if they just searched for terms they thought might be relevant to labour-relations, they would not capture as many terms as they would using automated semantic searches to find words associated with labour relations. Figure 1 below shows the extent to which they found parliament was discussing labour relations during the 19th and 20th century:

Figure 1 – Frequency of results concerning labour relations in House of Commons debates 1803-2005 (per million words).

Let us take the first half of the 19th century as an example. As can be gauged from the graph, there was very little discussion of labour relations during that period, with the exception of a small spike in the 1830s. When looking at historical events at that time, the researchers found this spike reflected two events: 1. Labour relations started to be debated after setting up trade unions was no longer deemed illegal, and 2. A specific debate about whether to send a group of agricultural workers to Australia after they had formed a kind of trade union to object to decreasing wages in their sector. Putting their initial corpus findings in this historical context helped them understand the way in which labour relations were discussed in that period.

Another, related, question they wanted to answer had to do with the different aspects of labour relations in parliamentary discourse. In particular, they wanted to know what importance they placed on each of the different aspects. They found that, throughout all the years represented in the Hansard corpus, parliamentarians talk most about trade unions as organisations, secondly about potentially disruptive actions like strikes, and only thirdly about the people involved in trade unions and in strikes. While they did not clearly state the consequences of these results, organisations such as trade unions, political parties, local authorities, campaigning and lobbying groups, think tanks and journalists might want to use information like this to support their work.

It is not difficult to see how corpus linguistic methodology might be useful for all kinds of interest groups. Our simplification of these methods will hopefully help readers understand that so much more can be done with databases of text than just searching for your own search terms. Future blogs will show more examples to help you start thinking about how you might use our Hansard tool.

Want to read more about the study Jane Demmen, Lesley Jeffries and Brian Walker undertook? This is its reference:

Demmen, J., Jeffries, L., & Walker, B. (2018). Charting the semantics of labour relations in House of Commons debates spanning two hundred years: A study of parliamentary language using corpus linguistic methods and automated semantic tagging. In M. Kranert, & G. Horan (Eds.), Doing Politics: Discursivity, Performativity and Mediation in Political Discourse (pp. 81-104). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

[Figure 1 has been reprinted from Charting the semantics of labour relations in House of Commons debates spanning two hundred years: A study of parliamentary language using corpus linguistic methods and automated semantic tagging (p. 92). By Demmen, J., Jeffries, L., & Walker, B. In M. Kranert, & G. Horan (Eds.), Doing Politics: Discursivity, Performativity and Mediation in Political Discourse (pp. 81-104). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. Copyright (2018) by John Benjamins Publishing. Used with permission.]